Dhahran Diary |

|||||||

|

|||||||

|

Title: Gabriel, Jeddy, and Chores DD05 |

|||||||

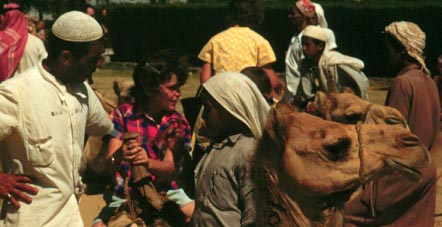

| JK had her admirers and she was not afraid to try new things like riding camels at the Fourth of July celebration at the Dhahran ball field.(rcc) | |||||||

|

|

|||||||

|

My school vacation routine (April, August, December) was to awaken early and read until Dad left for work. I’d have breakfast and head for the recreation area. If the family had just come back from long leave, which was 90 days, I had catch-up school until the first whistle (1130) each day. Then I was free to roam. If I did not have to attend classes, then I went to participate in one of the many student vacation programs designed to keep us busy and out of harm’s way. My parents were also helpful by getting me scheduled to travel with adults around the province. One program took us to various work sites to learn how ARAMCO ran its petroleum assets. Eventually summer jobs were available once we were old enough. I did not have to work in the house because we had a house boy. Actually we had several but not at the same time. Habib and Abdulla were ironers. They were both Arabs. Paul, an Indian houseboy, had worked for the British Raj; he cooked and cleaned. Later, Gabriel replaced him. He was from Goa. We had a gardener too, but this was short lived. My parents made it clear that the grass was my responsibility. Not the hedge though, that was Dad’s. He loved to get those electric clippers and trim the privet in a castle keep profile. I think he got the idea when we traveled through the subcontinent visiting various gardens with sculpted hedges around Bombay and Colombo. Most parents tried to give their children work at home to establish the work ethic. Many of us could not understand going to a friend's house only to be told he or she could not come out because they had to do chores! Choring was a foreign concept in Dhahran and the longer you lived in Saudi Arabia, the stronger your resistance became to menial labor. Most things were free ( or nominally free) within the compound, and this further distorted the Western value system. Our family had a Saudi Riyal money bag. If I needed money, I'd ask and Mom would tell me to get it from the bag. To me, money had little value. To JK, it meant even less because she was only four when we arrived in Dhahran. Eventually, ARAMCO began charging for the cinema, bowling, and the taxi, but the pool, wood shop, billiards, bus system--inter and intra--were all free. After years of service, the bowling alley still charged only a quarter of a riyal (a nickel) for shoe rental. So children growing up in that environment were surprised when they saw how everything was charged for in the real world. ARAMCO was truly a cash cow in the early days. Our parents' incomes were tax protected and ARAMCO gave every benefit imaginable to include travel expenses, long vacations, free furniture, and ultra-low rents. Everyone wanted to go on vacation but also wanted to get back just as soon as possible and begin salting the dollars away while living basically free. Paul was an excellent cook. Mom asked him to prepare certain things the family wanted but when Paul was left to his own hand, he created good food for all occasions. His Raj experience was evident in the way he would display and serve the food. Mashed potatoes were formed around the edge of the serving platter and the gravy was poured into the middle, making a lake. Little fried potatoes cut into diamond shapes were imbedded like jewels into the soft spuds. He had a little problem with our cat Booper; he didn’t want him in the kitchen. We’d hear the dish towel snap and Booper would come flying out with his ears back and his tail as big around as a fox’s in flight. Paul also liked his beverage too much. This was at a time when ARAMCO could have spirits for consumption within the camp. He did not serve cocktails, but when the glasses came back to the kitchen, he saved up the remains and had his own party later. Paul gave way to Gabriel. |

|||||||

Gabriel was short, quiet, and without obvious vices. He worked hard and we all knew he was saving to go back to Goa to take a wife. After several years, he quit and went back only to find arrangements had broken down. He reapplied with ARAMCO and came back to work with my parents until they retired in 1961.

Gabriel was gentle and always had a smile, unlike his employment picture. He made himself important to the family by providing assistance. We would be getting ready to leave on a trip and Gabriel was always remembering things we had forgotten.

When the three of us spent one year in the States and Dad batched it, Gabriel stayed with him and took care of his bachelor apartment. One week Dad went to al Karj where the experimental farms were located. The new apartment had a sticky lock and Gabriel broke the key off trying to get in one morning. He spent the rest of the week sitting on the back porch waiting for Dad to come home. He would never have thought to burden someone else with his problem. He went hungry the whole time.